So far in our study of Romans we have been introduced to the

theme of the letter—that God’s power is realized in the gospel of Jesus Christ.

Not only that, but we have begun to examine what the gospel looks like. A

couple of weeks ago, we recognized, via Romans 1, that an individual cannot be

saved until he/she recognizes his/her need for salvation. This is why Paul goes

to great lengths to describe how the pagans of this world are guilty before God

and in very real need of the salvation that only Jesus Christ can provide.

So far, so good right? People who live like the world

because they reject the revelation of God are going to hell. This is something that

many “God-fearing” churchgoers will readily say “amen” to. In fact, I received

several compliments after last Sunday’s sermon. Some even thanked me for

speaking frankly about what the Bible says concerning more obvious sins. However,

Paul doesn’t stop with the pagan. In chapter 2, he moves on to identify the guilt

of the religious before God—specifically, the religious Jew.

The religious Jew of Paul’s day might be compared to the

legalistic Christian today—those who were raised in the church and taught not

to drink, smoke, play cards, or run with girls who do. These are those who

congregate in their holy huddles only the bicker and complain about the very

world they are called to engage, clinging to tradition more than they do the

cross of Jesus Christ. These have a pretty face, but, as Jesus describes are

dead on the inside—“whitewashed tombs.” When I consider the archetypal legalist,

I think of John Lithgow’s character as the fundamentalist Baptist preacher in

the original Footloose. He believed

that as long as he could keep his daughter and the community from dancing and

listening to secular music, he had succeeded as a father and pastor. This

is the type of person that Paul addresses in chapter 2 of Romans as he

continues to identify the need of gospel in the world. Three comments that Paul

makes in Romans 2:1-5 indicate that it is not just the obviously “lost” who

need a savior. The resoundingly religious do as well.

1) Statement of

Culpability-2:1-2

Chapter 2 begins with clear transitional

marker—“therefore”—“Therefore, you have no excuse, every one of you who passes

judgment” (2:1a). Such a transition

demonstrates that Paul is now moving from explaining the guilt of the pagan

population to another group entirely. Having condemned the Gentiles from

suppressing the truth and falling victim to all kinds of evil after being

handed over to their sinful ways, Paul now intends to castigate Jews for their

own brand of failure.

However, the “you” here is singular. So just whom is Paul

addressing? The answer is found in verse 17. There it is clear that Paul means

to address the Jews in this chapter. So then, why does he single out one Jew

for the purposes of this discussion? The answer lies in a particular literary

device known as a diatribe that was commonly employed in Paul’s day. A diatribe

establishes a singular hypothetical individual that engages or is addressed by

an author for the benefit of those reading the exchange. Once established, the

readers are allowed to “listen in” to the discussion taking place and learn

from what is communicated therein. Here, Paul creates a hypothetical Jewish

individual that he can engage in an effort to teach a lesson to the Roman

church about the religiously minded (particularly, religious Jews).

Paul says that such a Jew (one “who passes judgment”) is

without excuse. Here, it is important to delineate exactly what is meant by

passing judgment. There are at least two different connotations associated with

judgment that are found in the New Testament. These two connotations might be

illustrated in the following two verses.

Matthew 7:1-5-“’Judge not, that you be not

judged. For with the judgment you pronounce you will be judged,

and with the measure you use it will be measured to you. Why do you

see the speck that is in your brother's eye, but do not notice the log

that is in your own eye? Or how can you say to your

brother, “Let me take the speck out of your eye,” when there is the log in your

own eye? You hypocrite, first take the log out of your own eye, and then you

will see clearly to take the speck out of your brother's eye.’”

John 7:24-“Do not judge according to appearance, but judge with righteous judgment.”

In the first passage (Matt. 7), it appears that to “judge”

involves “condemnation.” Such a view is supported by the idea that people need

to take care of their own faults before seeking to condemn others around them

for their issues. Inasmuch as God alone is perfect, he is the only one that

does not have to check himself before condemning those around him for

wrongdoing.

However, in the second passage (John 7:24), disciples are called

to “judge with righteous judgment.” Here, the term means to discern between

what is good and evil. Such discernment is not based, as the verse suggests, on

mere appearance, but the character of a thing, act, or person. Therefore, at

least two ideas can be represented in the verb for judge (krinw)—condemn and discern.

Of these two choices, the former (a condemning kind of

judgment) appears to be what Paul is taking to task. This is supported by what

he will eventually say in the remainder of the verse (see katakrinw in 2:1b) and is in sympathetic to

the character of the religious of his day. Many who would consider themselves

“religious” were quick to judge/condemn those around them—especially the pagan population

of Rome. Paul is calling out these in verse 1. These are without excuse.

Without excuse for what? For being just as guilty as the

very people they seek to condemn. Why?—“for in that which you judge another, you

condemn (katakrinw) yourself; for you

who judge practice the same things” (2:1b). In chapter 1 (especially verse 20)

the reader learned that Gentiles who rejected and suppressed the revelation of

God were without excuse and guilty. Here, one learns that the religious

(particularly religious Jews) who condemned those around them are also without

excuse (2:1). Those who judge are guilty of practicing the same things—more

literally rendered “habitually practicing”—that they condemn in others.

It is both anecdotally true and psychologically verified

that people tend to criticize those negative traits of which they themselves

are guilty. Psychologists call this projection. “Nothing blinds a person more

than the certainty that only others are guilty of moral faults” (Mounce, 88).

Martin Luther even noted “the unrighteous look for good in themselves and for

evil in others” (Romans, 36).

However, are the religious condemners really guilty of the

very same things the pagans are? Perhaps not on the surface, but certainly in

principle this is true. Though a religious bigot may not endorse homosexuality,

these understand what it is like to yearn for/desire that which is forbidden. Though

one might not murder someone, all know what it is like to harbor anger against

a neighbor (See Sermon on the Mount). Etc. Etc. Etc. Truly, in every way a

pagan is drawn to sin, so is the one who is righteous in his/her own eyes.

After all, every act of willful sin is rooted in idolatry and pride—“I know

better,” or “this means more to me than God does” in any given moment.

Therefore, when the nature of sin is exposed, both the pagan and religious are

guilty.

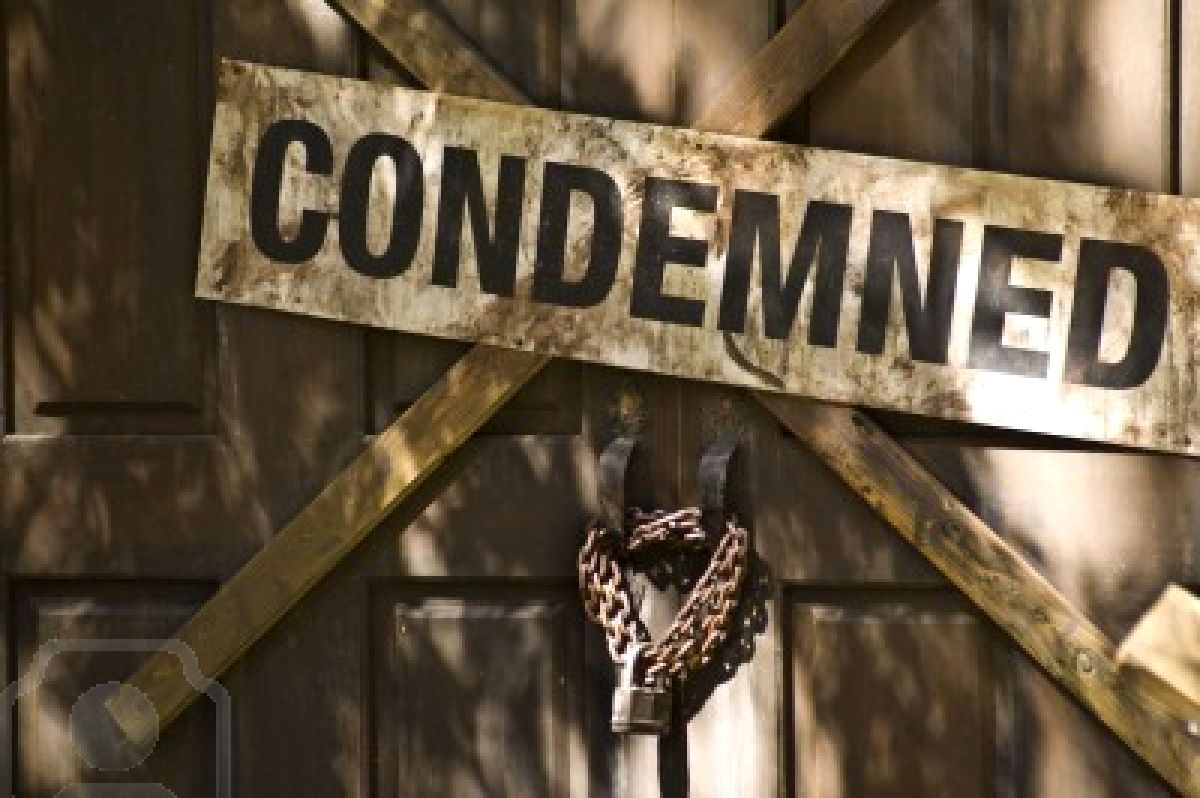

This is why Paul is able to say in verse 2 “and we know that

the judgment of God rightly falls upon those who practice such things” (2:2).

Here, those who are quick to condemn become the condemned before God.

One example of this is found in 2 Sam. 12:1-4. After

committing adultery with Bathsheba and covering up his failure by seeing to it

that her husband Uriah was killed in the line of duty, David is approached by

the prophet Nathan. The story reads as follows:

2 Sam. 12:1-14-“Then

the Lord sent Nathan to David. And he came to him

and said, ‘There were two men in one city, the one rich and the other

poor. The rich man had a great many flocks and herds. But the poor man had

nothing except one little ewe lamb which he bought and nourished; and it

grew up together with him and his children. It would eat of his bread and

drink of his cup and lie in his bosom, and was like a daughter to him. Now a

traveler came to the rich man, And he was unwilling to take from his own

flock or his own herd, to prepare for the wayfarer who had come to him; rather

he took the poor man’s ewe lamb and prepared it for the man who had come to

him.’ Then David’s anger burned greatly against the

man, and he said to Nathan, ‘As the Lord lives, surely the man who

has done this deserves to die. He must make

restitution for the lamb fourfold, because he did this thing and had no

compassion.’ Nathan then said to David, ‘You are the man!’”

In the same way David was guilty—so too are the purely

religious who seek to condemn those around them.

2) Questions for

Consideration-2:3-4

As Paul drives this point home, he asks his hypothetical

sparring partner a couple of rhetorical questions worthy of consideration. The

first of these is found in verse 3—“But do you suppose this, O man, when you

pass judgment on those who practice such things and do the same yourself, that

you will escape the judgment of God?” (2:3). The clear answer to this is “no!”

It does not matter who one is before God, those who sin are deserving of

judgment.

However, I’m sure there were those who were tempted to say

“yes” to this question, believing that they, in spite of their own sin, are

somehow not at risk of divine judgment. Perhaps these thought that their

ethnicity (being Jewish), or outward appearance before men kept them from

incurring God’s wrath. Paul says that this could not be further from the truth.

Unfortunately, many believe that they are somehow exempt

from God’s judgment today on the same grounds. “My parents went to church,” “I

give such and such to this or that,” “Everyone around me thinks I’m doing all right.”

Those with enough spiritual knowledge to render themselves dangerous have

always pretended that they are not the one with the problem. In fact, this is

addressed in Paul’s next question.

“Or do you think lightly of the riches of His kindness and

tolerance and patience, not knowing that the kindness of God leads you to

repentance?...” (2:4). “With this question, Paul gets to the heart of the

issue. Because of their covenant relationship with God, Jews frequently fell

into the habit of thinking that they were immune from the judgment of God”

(Moo, Zondervan Illustrated, 15). Unfortunately,

Paul’s hypothetical conversation partner, many religious Jews of his day, and

the spiritually-minded/religious of our own world are prone to misinterpret the

common grace and delay of wrath that God extends to everyone. These believe

that if things are going well, that must mean they themselves are doing morally

well also. However, with this haunting question, Paul calls this view out as

utter rubbish. These would do well not to interpret God's grace in their lives

as license. Instead, God’s kindness ought to lead one to repentance, not

licentiousness. After all, God “causes

His sun to rise on the evil and the good, and sends rain on the righteous and the unrighteous” (Matt. 5:45).

When people recognize all that God has allowed to transpire

in their lives, “the sun and the rain” if you will, then they should respond by

turning from their wicked ways, accepting what he has revealed, and glorifying

him in all that they do. Unfortunately, this does not always happen, especially

for the religious who believe that they have it all going on already!

This is why Paul is forced to explain their guilt in verse

5.

3) Explanation of

Guilt-2:5

Instead of being gently persuaded by God’s kindness to

recognize their sin and accept God’s gift of salvation, these are “stubborn and

unrepentant” (2:5a). What the reader has come to expect of the pagan is true of

the religious—a heart hardened against God! In chapter 1, this hardened heart

came by way of suppressing the truth and being handed over to sinfulness (after

these were given exactly what was asked for along with all of its implications).

In chapter 2, the hardened heart of the religious in general and the religious

Jew in particular came by way of misunderstanding the purpose of God’s grace,

and persistent condemnation of others.

“This truth has

serious implications. The person who knows but resists truth does not go away

from the encounter morally neutral. Truth resisted hardens the heart. It makes

it all the more difficult to recognize truth the next time around. Life is not

a game without consequences. By our response to God’s revelation we are

determining our own destiny.” (Mounce, 90).

As a result, these “are storing up wrath for [themselves] in

the day of wrath and revelation of the righteous judgment of God” (2:5b). Though

the Lord tarries in executing his judgment against the guilty, one day such

judgment will came. Ironically, the delay of divine retribution gives the

religious individual (that is one who is purely religious and devoid of any

relationship with God), more time to accumulate more wrath. Though many might

think their “goodness” and “many works” will impress God, those who

misunderstand God’s grace and are quick to condemn—proving that they are

unrighteous—will themselves receive condemnation at the appointed time (see

Psalm 110 and Revelation).

So What?

As Paul continues his letter, he is hoping that all

recognize their need for what only Jesus Christ can give. In chapter 1, he

explains the guilt and need of the pagan. In chapter 2, he explains the guilt

and need of the religious. This latter group is just as “lost” as the very

people these tend to condemn. In their condemnation of others, they condemn

themselves. While they have been shown great grace, they are not humbled toward

repentance. Instead, these believe they have some kind of claim on

righteousness. Do not be fooled, God grace is intended to lead the sinner to

repentance, not self-righteousness.

Paul presents these comments in Romans 2:1-5 so that those

attending the church understand that religiosity and legalism is not enough. In

fact, those who are merely religious are just as far gone as the pagans. How

might we tell if Paul is describing us in this passage? Ask yourself, am I

quick to condemn others in an effort to make myself look/feel better? Am I

quietly entertaining and endorsing what others do out in the open? Do I believe

that I’m free to do as I please? If your answer is “yes,” consider the very

real possibility that you might need to trade your religion for a real

relationship with Jesus Christ.

May it not be said of any of us—that we were merely

religious, devoid of any real relationship with Lord.

No comments:

Post a Comment